Well, my friends, summer approaches. And as many of us (like our favorite television shows) go on hiatus, it occurs to me that there will be many long hours spent on planes and in cars that must be filled one way or another. As my own commute has increased, I myself have found that I sometimes desire a bit more than music on the road. Fortunately, I have also acquired a delightful source of entertainment: audiobooks.

For a large chunk of my childhood, during the countless sweltering days of Texas summer that were simply too hot to face, my siblings and I would select the house’s coolest room and lie scattered over the floor without moving a single limb (unless we felt like budging one arm to build with Lego® Blocks on the side). And while we lounged about, we would listen to books on tape. While there were plenty of series to choose from, there was one classic selection that was virtually inexhaustible: Redwall.

I may have had over a decade to fall in love with the never-ending saga, but some of you may not have that kind of time on your hands. That’s why I’m going to provide you with this thorough, spoiler-free explanation of why you just might want to look into a series about sword-wielding rodents.

Hogwarts Redwall, A History

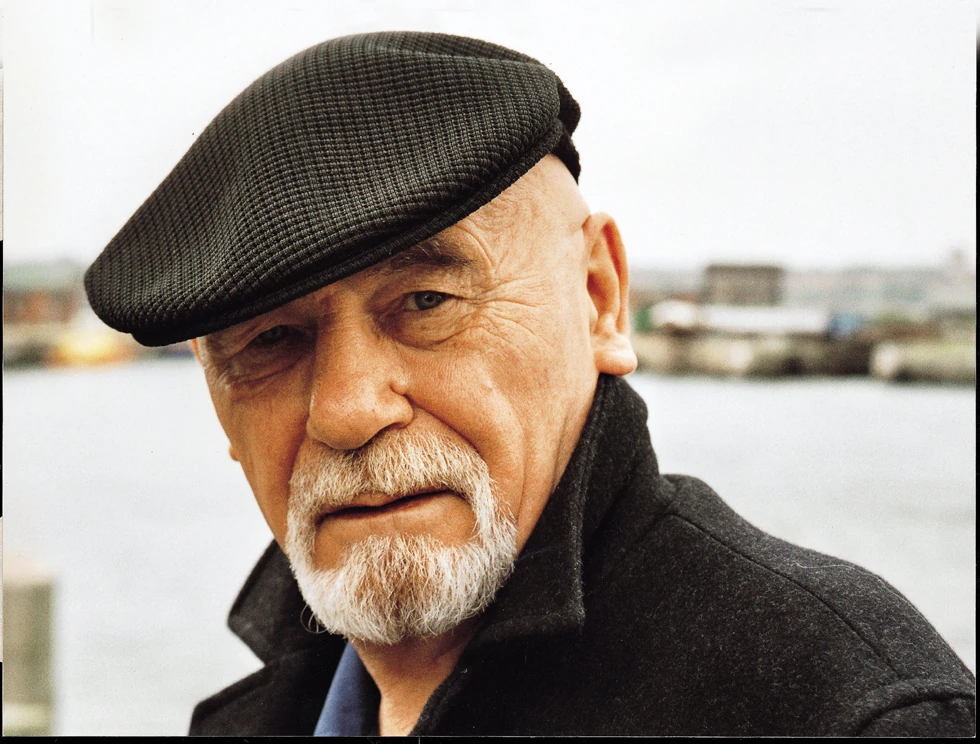

Though the first Redwall book was published in 1986, the story of its origin actually begins decades earlier with the author — a Liverpool native by the name of James Brian Jacques (pronounced “Jakes”). He grew up near the town docks and soaked in the knowledge of the many travelers that came in to berth, which merely enhanced his love for reading books like Sherlock Holmes and Treasure Island. After he finished school, he made his way out into the world as a jack of all trades: sometimes on the high seas as a sailor, sometimes driving a simple delivery truck.

Of all the jobs that Jacques performed, the one that changed his future was his hobby of reading aloud to children at the Royal Wavertree School for the Blind. He took an immediate dislike to their curriculum, which was full of angsty adolescent novels and very little in the way of enchanting adventures. Instead, as he often explained to fans, he started writing his own stories for the kids: something with a touch of fantasy and magic, with strong descriptive words that focused on more than just visual experiences.

The resulting 800-page manuscript was universally lauded as a priceless children’s tale, despite its size (and audiences warmed to lengthy children’s books after the rise of other series like Harry Potter at the start of the new millennium). Jacques wrote of medieval warriors and peasants, but changed the characters into anthropomorphic animals (such as mice and squirrels) because, as he said, “Mice are my heroes because, like children, mice are little and have to learn to be courageous and use their wits.”

As time went on, Jaques published twenty-one books in the Redwall saga (along with other books including his classic seafaring legend, Castaways of the Flying Dutchman). A graphic novel adaptation of Redwall's first book was published in 2007. Jacques even teamed up with the BBC to create recorded audiobooks (of all but five of his Redwall novels) in which he was the chief narrator, and various actors played the roles of his colorful characters. In fact, my initial writing style stemmed largely from Jacques, as I spent countless hours listening to his rich narrations until even my thoughts were all in deep Scottish Sean-Connery-esque brogue.

BBC One (or PBS in America) also aired a brief animated series about Redwall starting in 1999. Each of the three seasons focused on one of the major books in the saga (one even featured Tim Curry as the head villain) using some slightly sub-par animation. Despite a positive fan response, there was no fourth season for financial reasons.

Over ten attempts to create a feature film have been rumoured for the past decade, but all have fizzled out (though fresh, un-backed whispers about a videogame have also surfaced).

Over ten attempts to create a feature film have been rumoured for the past decade, but all have fizzled out (though fresh, un-backed whispers about a videogame have also surfaced).

Jacques continued writing for the rest of his life, and he was my favorite living author until his tragic death in 2011. Though only one last Redwall book has been posthumously published, I still get the chance to savor his presence and renew my passion for writing whenever I pull out my dusty cassette tapes (or just, you know, open iTunes).

The Plot

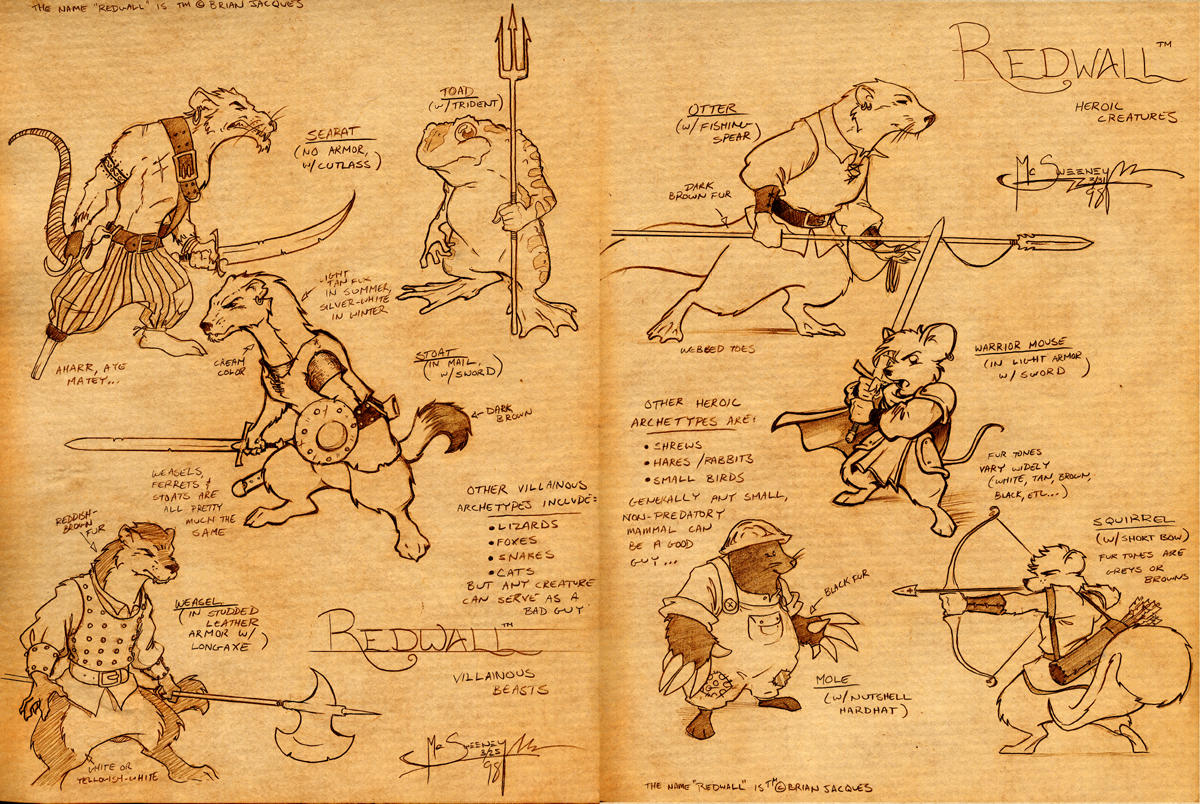

The great challenge of creating a 22-book series is the fact that one simply cannot write them all about the same group of main characters. As a result, Redwall does not follow one single storyline that can be adequately summarized. However, the heart of the stories are much the same: they focus on young male and female protagonists — some mice, some squirrels, some badgers, and so forth — as they find themselves suddenly face to face with evil that lays threat against all that is good in their world: slavers, warlords, monsters, and even just simple bullies.

Rather than centering these events around a great or legendary castle, Jacques chose instead for the stories to converge around “Redwall Abbey,” a rosey sandstone edifice of peace and plenty, rather than war and work. The figurehead of the abbey is the legendary mouse Martin the Warrior, who freed the inhabitants of the woodlands and eventually laid down his renowned sword to become a creature of peace. Some of the books tell of his origins; others of the distant mountain Salamandastron where badger warlords reign over military hares. But even in stories where the abbey is absent, Martin’s spirit is often present and guiding the lives of righteous peasant creatures through the centuries. In fact, Jacques’ Catholic upbringing had a noticeable influence on his themes, which focus little on religion but do often run thick with mentions of destiny and inherent chivalry.

Some of his earliest versions of the Redwall universe hint at the existence of humans on the margins of the world, describing the abbey as if too big for actual rodents, or mentioning a horse towing a cart filled with over a hundred rats. However, as he explored this world of his, human presence went to the wayside and the animal characters became the major inhabitants of the land.

Jacques based numerous characters in the books off of people he himself encountered, be they family or old friends from his distant travels as a sailer. Every type of creature in the series has its own culture, dialect, and personality (and fans often try to decide what creature they would be in the series, much like Harry Potter fans sorting themselves into Hogwarts houses). Hares are posh military chaps with a strong sense of duty; otters are rough-and-tumble sailors; moles are sometimes naive but fiercely loyal and innovative; mice are small but willing to always do the right thing; and the list goes on.

Jacques also makes clear distinctions between goodbeasts (mice, moles, hedgehogs, badgers, etc.) and bad (rats, weasels, wildcats, etc.) and paints for children a very black and white portrayal of morality. One might almost say that he’s “racist” by not giving many of the ‘evil’ species a chance at redemption in most cases, but I think his intentions were not to set his readers against a certain animal. Rather, Jacques pointedly shows children what good and evil personalities look like, so that in a world where everyone is human, they may still be able to recognize cowardice or selfishness in someone else and realize, “perhaps that person would be a rat if they were in Redwall. I ought to be brave and not behave like them.”

The Appeal

Readers have returned to the Redwall series again and again for many reasons, but the heart of the matter is that Jacques was one of the greatest writers of his time. His absolute mastery of the English language is evident (and I know for a fact that my adolescent vocabulary expanded extensively thanks to his work). He often narrates in a way that introduces new words to his young readers, using scattered synonyms until they're able to recognize the meaning of his fancy terms.

Poetry, riddles, and original ballads abound (which are especially enjoyable on the audiobooks, where the songs are actually performed). Jacques’ experiences during World War II also inspired two things in the novels that don’t seem to go hand-in-hand. For one, his battles are gruesomely realistic and perilous. But for another, he describes food with a surprising amount of detail. Jacques often mused that during his childhood, heroes in stories would sit down to great feasts — to which he (as a hungry boy during Britain’s rationing campaign) always wondered in frustration, “But what was the feast!?”

So in Redwall, every meal is described in detail: trifles, scones, cheeses, ales, pies, stews, and more — ensuring a drooling audience that will likely go purchase their own copy of The Redwall Cookbook before he’s finished with them. And yet he goes even further than that.

Jacques not only mentions that his characters make a fire or a javelin or a massive cake; thanks to his years spent abroad, he can describe every step in detail until his readers know how to accomplish those same things for themselves. He tells of herbal remedies for sicknesses and poison; military and guerrilla tactics; sailing tips; and even gardening methods. Jacques is a master writer of adventures because he himself has lived adventures, and his writings teach in detail how such legendary journeys can be had by anyone. Myths are only valuable when they feel real enough to be experienced, and Jacques has accomplished that semblance of reality more than any other author I’ve ever known. Whether it’s a perilous journey through the mountains or a voyage on the high seas, Jacques paints vivid pictures with his words until the audience feels as if they’ve tramped through Mossflower Wood for themselves.

The Rating

I’d say the series is probably PG-13, though book violence certainly differs from cinematic violence. The tales are 90% child-friendly, but they don’t shy away from portraying bloodthirsty, malicious villains and deadly graphic wars.

Violence: While blood and guts may not be extensively glorified, battles and death and torture are still a very real thing. A warrior’s life is lauded, but also shown to be tragic and personally impactful. Characters fall on all sides, good and bad, guilty and innocent: some are crushed, impaled, cut in half, and one character is very nearly skinned alive. As Jacques himself mentioned, he didn’t want children to be ignorant of evil — but rather, to be able to recognize it and know that it could be defeated.

Sex: None. Characters are occasionally married and babies are born, but this very Disney-esque fantasy portrays little more than the occasional kiss.

Language: There’s little to nothing serious (especially for American readers who aren’t as sensitive to British slang), but some creatures are very creative in their verbal attacks on one another, and younger more impressionable children may start using the term “Mister Snottynose,” or “Fat-Bellied Toad” as their new favorite insult.

Spiritual Content: While very little is present for the most part, there are some antagonists who trust in seers and magicians for guidance — and the inhabitants of Redwall follow the guidance of Martin the Warrior when he appears to them in dreams. There are also rare mentions of the afterlife, either in a “Dark Forest” with legendary ancestors or at the gates of Hell, but they’re not major influences on anyone’s behavior.

The Genre

Redwall is a classic tale of high adventure and medieval fantasy, which takes its readers on all sorts of incredible journeys. Having anthropomorphic animals as the characters is just icing on the cake for younger children (or for adults who feel like enjoying a spot of whimsy). It focuses on the need for courage against injustice, the duty of sacrifice for the sake of others, and the drive for dignity in the face of corruption. It may seem like the petty makings of a fairytale yarn, but our world is all-too-deprived of good solid fairytales (and well-written books).

So is it worth it?

The Decision

That depends on you. My childhood days had far more free hours of time than my current adult ones, and so my ability to read for leisure has been much-lessened over the years. Many of my peers have the same problem. However, thanks to the Redwall BBC audiobooks, many of my long solitary road trips have been not only endured, but enjoyed (though granted, I tend to enjoy road trips anyway). Even if your schedule is too crammed for a book, hopefully there are a few minutes each day when you can listen to a jovial Scottish master-author as he weaves vivid pictures using his incredible command of the English language and his history as a merchant sailor and adventurer on the high seas. Redwall isn’t meant to be particularly challenging morally or intellectually — it’s meant to be enjoyed.

And if you’re worried about getting lost amid the twenty-two different novels, there are plenty of different places to start. Most of the plots occur without really relating to one another, and it’s rare for any story to feature the same characters as a previous one.

If you wish to start with the very first book published, then Redwall is of course your best option. This first book was made to induct readers into the series, so you can read it without fear of not understanding any context. Jacques may still be finding his footing in the genre, but that’s okay; you will be, too. This book was also featured as the subject for the television show’s first season.

Mattimeo

This book follows on the heels of Redwall and deals with the next generation of Redwallers as they face a new threat. There are some returning characters from the original book, and Mattimeo was also the focus of the television show’s second season.

Featured in the third season of the television series, this book unwraps the origins of Redwall’s famed hero and figurehead, long before the abbey was ever built.

Mossflower

Still following Martin on his long life’s journey, this book shows a little more about how the hero arrived in the Mossflower woodlands where the abbey would eventually stand, and how he came to free the creatures there.

The Chronological Beginning

Lord Brocktree

If you want to start with the genesis of Jacque’s world and see his universe built piece by piece, this tale of a badger lord is where everything begins. You can find a full list of the books in chronological order on informational sites like Wikipedia.

Good stand-alone books, in most cases, require next to no information except the basics already explained in this article. They’re great for giving somebody a taste of the greatest entertainment Redwall has to offer, for those who don’t want to wade through several different novels to decide whether they like the saga. However, just about every fan of Jacques has a different favorite book and a checkmate argument for why it’s the best for newcomers. I won’t pretend that my personal favorite, The Taggerung, is better than anyone else’s (though I cannot stop reading it over and over and over), so I recommend that you ask the nearest Redwall fan in your life where they think you should start.

Trailers and Previews

Redwall was meant to be read and not watched, but if you reeeally want a taste of what the television show was like then you can take a look at this fan-made trailer pieced together from clips of the show.

0 comments:

Post a Comment